Page path:

- Press Office

- Press releases 2012

- 22.05.2012 Rapid Coral Death

22.05.2012 Rapid Coral Death

Rapid Coral Death by a Deadly Chain Reaction

Soil Erosion in Tropical Coastal Areas Accelerates Coral Death

Most people are fascinated by the colorful and exotic coral reefs, which form habitats with probably the largest biodiversity. But human civilisation is the top danger to these fragile ecosystems through climate change, oxygen depletion and ocean acidification. Industrialisation, deforestation and intensive farming in coastal areas are changing dramatically the conditions for life in the oceans. Now Max Planck Scientists from Bremen together with their colleagues from Australia, Sultanate of Oman and Italy have investigated how and why the corals die when exposed to sedimentation. They published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

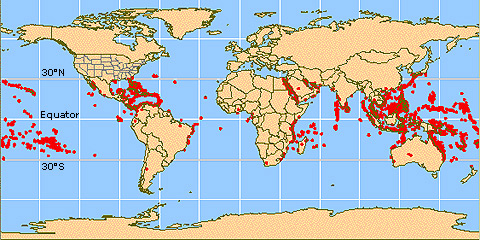

Reef forming stone corals inhabitat the light-flooded tropical shallow coastal regions 30 degree south and north of the equator. Coral polyps build the carbonate skeletons that form the extensive reefs over hundreds to thousands of years. Photosynthesis of the symbiotic algae inside the polyps produces oxygen and carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water, thereby feeding the polyps.

Soil Erosion in Tropical Coastal Areas Accelerates Coral Death

Most people are fascinated by the colorful and exotic coral reefs, which form habitats with probably the largest biodiversity. But human civilisation is the top danger to these fragile ecosystems through climate change, oxygen depletion and ocean acidification. Industrialisation, deforestation and intensive farming in coastal areas are changing dramatically the conditions for life in the oceans. Now Max Planck Scientists from Bremen together with their colleagues from Australia, Sultanate of Oman and Italy have investigated how and why the corals die when exposed to sedimentation. They published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Reef forming stone corals inhabitat the light-flooded tropical shallow coastal regions 30 degree south and north of the equator. Coral polyps build the carbonate skeletons that form the extensive reefs over hundreds to thousands of years. Photosynthesis of the symbiotic algae inside the polyps produces oxygen and carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water, thereby feeding the polyps.

On the left picture is an intact reef located in coastal waters of the far northern Great Barrier Reef. In the catchment on land the natural vegetation is predominant. On the right picture is an impacted reef close to an urbanised coastal area in North Queensland, Australia. (© M. Weber/HYDRA Institute/Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript])

Miriam Weber measures the oxygen concentration with hair-fine microsensors in a sediment layer, where the sediment was accumulated. If the organic load is increased in the two millimeter layer of sediments, the killing process will start. Blocked off from the light the algae will stop producing oxygen, microorganisms will start to decompose the organic matter, hydrogen sulfide is produced and kills the remaining cells. (© C. Lott/HYDRA Institute/Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript])

Coral Bleaching, the slow demise

Since the 1980s the process of coral bleaching is under study: elevated temperatures of 1 to 3 degrees induce the algae to produce toxins. The polyps react by expelling the algae and the coral reef loses its color as if it was bleached. Without its symbionts the coral can survive only several weeks.

Rapid death in less than 24 hours

In coastal areas with excessive soil erosion where rivers flush nutrients, organics and sediments to the sea, corals can die quickly when exposed to sedimentation. Miriam Weber, scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, explains the scientific approach.“Our idea was that a combination of enhanced deposition of sediments with elevated organic matter load and naturally occuring microorganisms can cause the sudden coral death. To get a handle on the diverse physical, chemical and biological parameters we performed our experiments at the Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) in Townsville under controlled conditions in large containers (mesocosms), mimicking the natural habitat.“

The team of researchers found out the crucial steps:

Phase 1: When a two millimeter layer of sediment enriched with organic compounds covers the corals, the algae will stop photosynthesis, as the light is blocked.

Phase 2: If the sediments are organically enriched, then digestion of the organic material by microbial activity reduces oxygen concentrations underneath the sediment film to zero. Other microbes take over digesting larger carbon compounds via fermentation and hydrolysis thereby lowering the pH.

Phase 3: Lack of oxygen and acidic conditions harm small areas of coral tissue irreversibly. The dead material is digested by microbes producing hydrogen sulfide, a compound that is highly toxic for the remaining corals. The process gains momentum and the remainder of the sediment-covered coral surface is killed in less than 24 hours.

Since the 1980s the process of coral bleaching is under study: elevated temperatures of 1 to 3 degrees induce the algae to produce toxins. The polyps react by expelling the algae and the coral reef loses its color as if it was bleached. Without its symbionts the coral can survive only several weeks.

Rapid death in less than 24 hours

In coastal areas with excessive soil erosion where rivers flush nutrients, organics and sediments to the sea, corals can die quickly when exposed to sedimentation. Miriam Weber, scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, explains the scientific approach.“Our idea was that a combination of enhanced deposition of sediments with elevated organic matter load and naturally occuring microorganisms can cause the sudden coral death. To get a handle on the diverse physical, chemical and biological parameters we performed our experiments at the Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) in Townsville under controlled conditions in large containers (mesocosms), mimicking the natural habitat.“

The team of researchers found out the crucial steps:

Phase 1: When a two millimeter layer of sediment enriched with organic compounds covers the corals, the algae will stop photosynthesis, as the light is blocked.

Phase 2: If the sediments are organically enriched, then digestion of the organic material by microbial activity reduces oxygen concentrations underneath the sediment film to zero. Other microbes take over digesting larger carbon compounds via fermentation and hydrolysis thereby lowering the pH.

Phase 3: Lack of oxygen and acidic conditions harm small areas of coral tissue irreversibly. The dead material is digested by microbes producing hydrogen sulfide, a compound that is highly toxic for the remaining corals. The process gains momentum and the remainder of the sediment-covered coral surface is killed in less than 24 hours.

Miriam Weber: „First we thought that the toxic hydrogen sulfide is the first killer, but after intensive studies in the lab and mathematical modeling we could demonstrate that the organic enrichment is the proximal cause, as it leads to lack of oxygen and acidification, kicking the corals out of their natural balance. Hydrogen sulfide just speeds up the spreading of the damage. We were amazed that a mere 1% organic matter in the sediments is enough to trigger this process. The extreme effect of the combination of oxygen depletion and acidifation are of importance, keeping in mind the increasing acidification of the oceans. If we want to stop this destruction we need some political sanctions to protect coral reefs.“

Katharina Fabricius from the AIMS adds:“ This study has documented for the first time the mechanisms why those sediments that are enriched with nutrients and organic matter will damage coral reefs, while nutrient-poor sediments that are resuspended from the seafloor by winds and waves have little effect on reef health. Better land management practices are needed to minimise the loss of top soil and nutrients from the land where they are beneficial, and are not being washed into the coastal sea where they can cause so much damage to inshore coral reefs.“

Manfred Schloesser

Katharina Fabricius from the AIMS adds:“ This study has documented for the first time the mechanisms why those sediments that are enriched with nutrients and organic matter will damage coral reefs, while nutrient-poor sediments that are resuspended from the seafloor by winds and waves have little effect on reef health. Better land management practices are needed to minimise the loss of top soil and nutrients from the land where they are beneficial, and are not being washed into the coastal sea where they can cause so much damage to inshore coral reefs.“

Manfred Schloesser

For more information please contact

Dr. Miriam Weber, HYDRA Field Station/Centro Marino Elba, office +39 0565 988 027, Mobil +39 338 937 56 77, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Dirk de Beer, Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, office +49 421 2028 802, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Katharina Fabricius, AIMS Principal Research Scientist, k.fabricius aims.gov.au

or the press officers of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Dr. Manfred Schloesser, +49 421 2028704, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Rita Dunker, +49 421 2028856, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Miriam Weber, HYDRA Field Station/Centro Marino Elba, office +39 0565 988 027, Mobil +39 338 937 56 77, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Dirk de Beer, Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, office +49 421 2028 802, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Katharina Fabricius, AIMS Principal Research Scientist, k.fabricius aims.gov.au

or the press officers of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Dr. Manfred Schloesser, +49 421 2028704, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Rita Dunker, +49 421 2028856, [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Original article

Mechanisms of damage to corals exposed to sedimentation

Miriam Weber, Dirk de Beer, Christian Lott, Lubos Polerecky, Katharina Kohls, Raeid M. M. Abed, Timothy G. Ferdelman, and Katharina E. Fabricius. PNAS 10.1073/pnas.1100715109 PNAS May 21, 2012

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/05/18/1100715109.abstract

Scientific Institutes

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, 28359 Bremen, Germany

HYDRA Institute for Marine Sciences, Elba Field Station, 57034 Campo nell’Elba,

Italy;

Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Queensland 4810, Australia

Biology Department, College of Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat 123, Sultanate of Oman

Mechanisms of damage to corals exposed to sedimentation

Miriam Weber, Dirk de Beer, Christian Lott, Lubos Polerecky, Katharina Kohls, Raeid M. M. Abed, Timothy G. Ferdelman, and Katharina E. Fabricius. PNAS 10.1073/pnas.1100715109 PNAS May 21, 2012

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/05/18/1100715109.abstract

Scientific Institutes

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, 28359 Bremen, Germany

HYDRA Institute for Marine Sciences, Elba Field Station, 57034 Campo nell’Elba,

Italy;

Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Queensland 4810, Australia

Biology Department, College of Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat 123, Sultanate of Oman