- Press Office

- Press releases 2022

- Sweet spots in the sea: Mountains of sugar under seagrass meadows

Sweet spots in the sea: Mountains of sugar under seagrass meadows

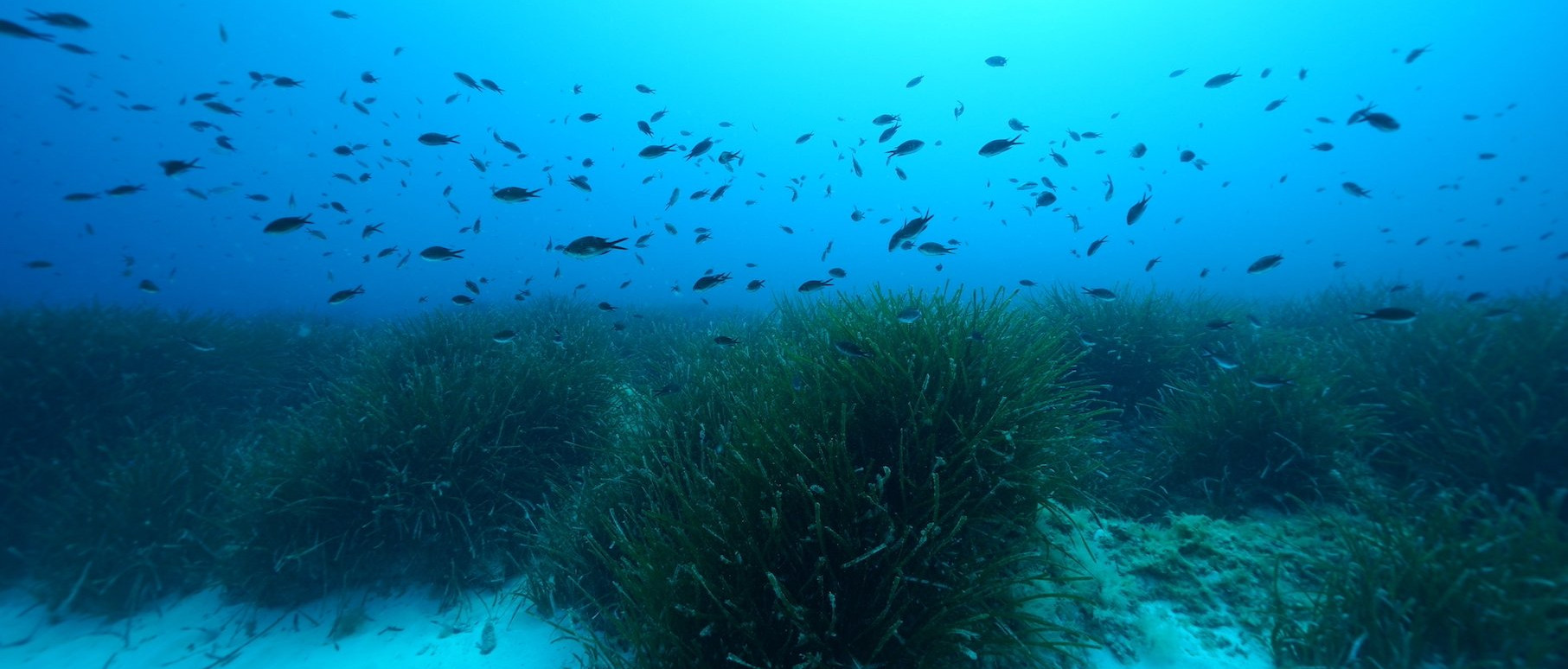

Seagrasses form lush green meadows in many coastal areas around the world. These marine plants are one of the most efficient global sinks of carbon dioxide on Earth: One square kilometer of seagrass stores almost twice as much carbon as forests on land, and 35 times as fast. Now scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, have discovered that seagrasses release massive amounts of sugar into their soils, the so-called rhizosphere. Sugar concentrations underneath the seagrass were at least 80 times higher than previously measured in marine environments. “To put this into perspective: We estimate that worldwide there are between 0.6 and 1.3 million tons of sugar, mainly in the form of sucrose, in the seagrass rhizosphere”, explains Manuel Liebeke, head of the Research Group Metabolic Interactions at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology. “That is roughly comparable to the amount of sugar in 32 billion cans of coke!”

Polyphenols keep microbes from eating the sugar

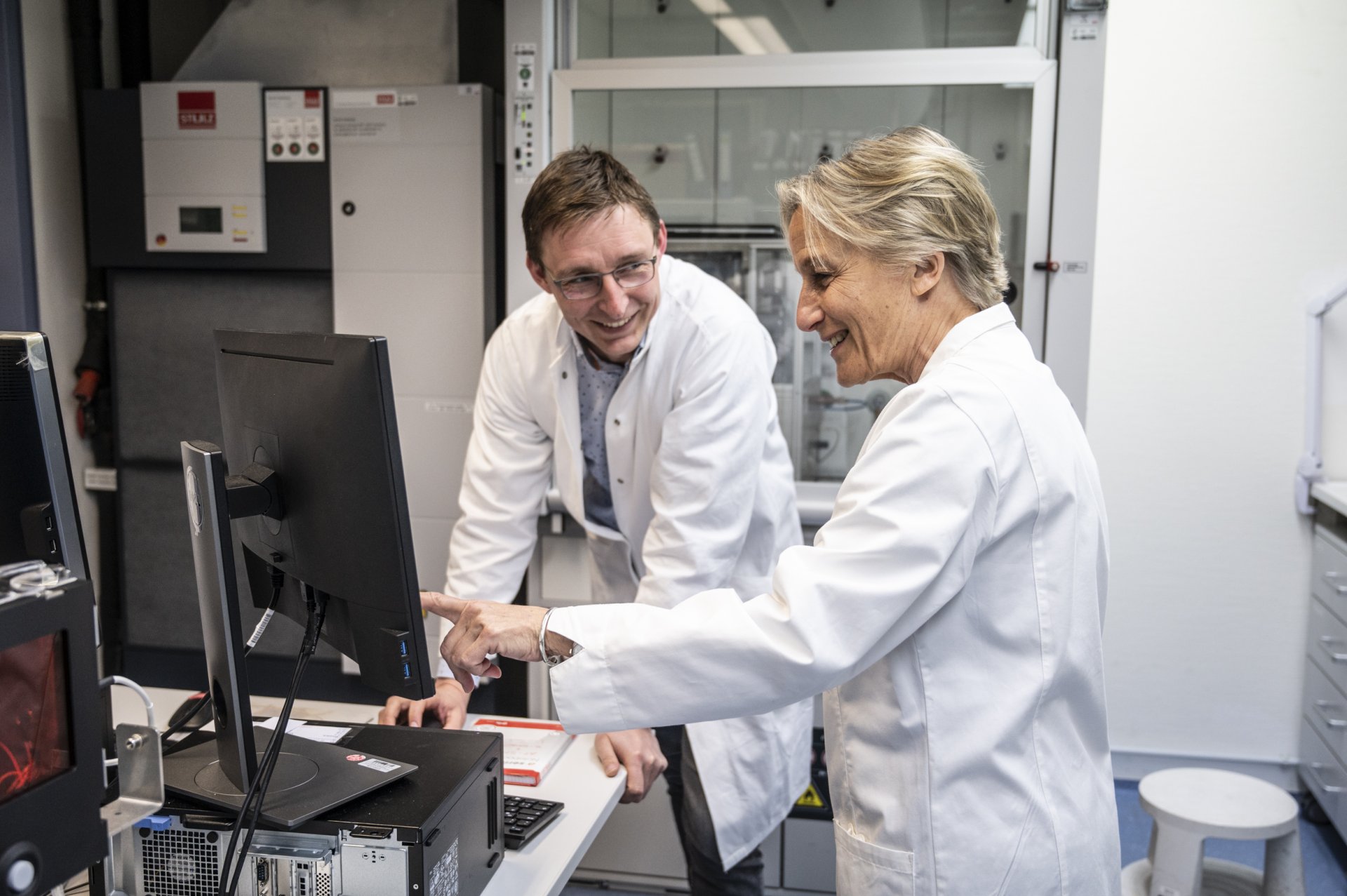

Microbes love sugar: It is easy to digest and full of energy. So why isn't the sucrose consumed by the large community of microorganisms in the seagrass rhizosphere? “We spent a long time trying to figure this out”, says first author Maggie Sogin, who led the research off the Italian island of Elba and at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology. “What we realized is that seagrass, like many other plants, release phenolic compounds to their sediments. Red wine, coffee and fruits are full of phenolics, and many people take them as health supplements. What is less well known is that phenolics are antimicrobials and inhibit the metabolism of most microorganisms. “In our experiments we added phenolics isolated from seagrass to the microorganisms in the seagrass rhizosphere – and indeed, much less sucrose was consumed compared to when no phenolics were present.”

Some specialists thrive on sugars in the seagrass rhizosphere

Why do seagrasses produce such large amounts of sugars, to then only dump them into their rhizosphere? Nicole Dubilier, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology explains: “Seagrasses produce sugar during photosynthesis. Under average light conditions, these plants use most of the sugars they produce for their own metabolism and growth. But under high light conditions, for example at midday or during the summer, the plants produce more sugar than they can use or store. Then they release the excess sucrose into their rhizosphere. Think of it as an overflow valve”.

Intriguingly, a small set of microbial specialists are able to thrive on the sucrose despite the challenging conditions. Sogin speculates that these sucrose specialists are not only able to digest sucrose and degrade phenolics, but might provide benefits for the seagrass by producing nutrients it needs to grow, such as nitrogen. “Such beneficial relationships between plants and rhizosphere microorganisms are well known in land plants, but we are only just beginning to understand the intimate and intricate interactions of seagrasses with microorganisms in the marine rhizosphere”, she adds.

Endangered and critical habitats

Seagrass meadows are among the most threatened habitats on our planet. “Looking at how much blue carbon – that is carbon captured by the world's ocean and coastal ecosystems – is lost when seagrass communities are decimated, our research clearly shows: It is not only the seagrass itself, but also the large amounts of sucrose underneath live seagrasses that would result in a loss of stored carbon. Our calculations show that if the sucrose in the seagrass rhizosphere was degraded by microbes, at least 1,54 million tons of carbon dioxide would be released into the atmosphere worldwide”, says Liebeke. "That's roughly equivalent to the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by 330,000 cars in a year." Seagrasses are rapidly declining in all oceans, and annual losses are estimated to be as high as 7% at some sites, comparable to the loss of coral reefs and tropical rainforests. Up to a third of the world’s seagrass might have been already lost. “We do not know as much about seagrass as we do about land-based habitats”, Sogin emphasizes. “Our study contributes to our understanding of one of the most critical coastal habitats on our planet, and highlights how important it is to preserve these blue carbon ecosystems."

Original publication

E. Maggie Sogin, Dolma Michellod, Harald Gruber-Vodicka, Patric Bourceau, Benedikt Geier, Dimitri V. Meier, Michael Seidel, Soeren Ahmerkamp, Sina Schorn, Grace D‘Angelo, Gabriele Procaccini, Nicole Dubilier, Manuel Liebeke: Sugars dominate the seagrass rhizosphere. Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)

Participating institutions

- Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

- University of California at Merced, CA, USA

- University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

- Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn Napoli, Naples, Italy

Please direct your queries to:

Group leader

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3244 |

|

Phone: |

Director

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3241 |

|

Phone: |

Dr. E. Maggie Sogin

Assistant Professor

University of California, Merced, USA

Phone: +1-508-566-5933

Email: [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |