Page path:

- Press Office

- Press releases 2011

- 26.07.2011 Nitrogen losses off the Coast of Oman

26.07.2011 Nitrogen losses off the Coast of Oman

Bremen, 26 July 2011

Intensive Nitrogen losses off the coast of Oman

Caused by Coupling of two microbial processes

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient and often a limiting factor for all life on our planet. It is present in proteins and DNA. In the oceans, microbial processes regulate the concentrations and fluxes of biological relevant nitrogen compounds like ammonia, nitrite and nitrate, which have to be available for the marine life. The major sink through which nitrogen can escape from the marine food web into the atmosphere is as nitrogen gas, N<sub>2</sub>. The driving forces balancing this system are more complex than previously thought. Now scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and their colleagues have taken a very close look at the microbial processes in the Arabian Sea and published their results in two scientific papers.

The marine food web stores huge amounts of organic carbon compounds. The carbon cycle is interacting with both the dissolved molecular oxygen (O<sub>2</sub>) and the nitrogen cycle. Global warming results in a diminished solubility of oxygen, and the influx of waste-water loaded with organic compounds from the human civilization further consumes oxygen. Consequently, the oxygen-deficient waters or oxygen minimum zones (OMZ), which originally constituted only <<1% global ocean volume yet responsible for 30-50% of the global marine N-losses, have been spreading worldwide in the last few decades. More N-losses will thus be expected.

The Arabian Sea harbors one of the three largest OMZs in the world and about 10-20 % of all global marine N-losses is thought to happen there. Thus far, it has been regarded as a fact that a bacterial process called denitrification was the major pathway resulting in N-losses from the Arabian Sea, via the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrite, then to nitric oxide, nitrous oxide and eventually gaseous nitrogen N<sub>2</sub>. Earlier studies from other authors claimed low oxygen and simultaneously high nitrite concentrations to be an indicator for denitrification and subsequent N-losses, but actual activity measurements have been rare. To solve this puzzle, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology including Phyllis Lam, Marlene Jensen and Marcel Kuypers, teamed up with scientists from Kiel, Oldenburg, Hamburg, Aarhus (Denmark), Nijmegen, (the Netherlands) and Princeton (USA), to trace the individual reaction steps in the nitrogen cycle by following the fate of compounds labeled with the stable isotope of <sup>15</sup>N. Additionally, they identified the responsible microorganisms and active expression of the corresponding biomarker genes.

Intensive Nitrogen losses off the coast of Oman

Caused by Coupling of two microbial processes

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient and often a limiting factor for all life on our planet. It is present in proteins and DNA. In the oceans, microbial processes regulate the concentrations and fluxes of biological relevant nitrogen compounds like ammonia, nitrite and nitrate, which have to be available for the marine life. The major sink through which nitrogen can escape from the marine food web into the atmosphere is as nitrogen gas, N<sub>2</sub>. The driving forces balancing this system are more complex than previously thought. Now scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and their colleagues have taken a very close look at the microbial processes in the Arabian Sea and published their results in two scientific papers.

The marine food web stores huge amounts of organic carbon compounds. The carbon cycle is interacting with both the dissolved molecular oxygen (O<sub>2</sub>) and the nitrogen cycle. Global warming results in a diminished solubility of oxygen, and the influx of waste-water loaded with organic compounds from the human civilization further consumes oxygen. Consequently, the oxygen-deficient waters or oxygen minimum zones (OMZ), which originally constituted only <<1% global ocean volume yet responsible for 30-50% of the global marine N-losses, have been spreading worldwide in the last few decades. More N-losses will thus be expected.

The Arabian Sea harbors one of the three largest OMZs in the world and about 10-20 % of all global marine N-losses is thought to happen there. Thus far, it has been regarded as a fact that a bacterial process called denitrification was the major pathway resulting in N-losses from the Arabian Sea, via the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrite, then to nitric oxide, nitrous oxide and eventually gaseous nitrogen N<sub>2</sub>. Earlier studies from other authors claimed low oxygen and simultaneously high nitrite concentrations to be an indicator for denitrification and subsequent N-losses, but actual activity measurements have been rare. To solve this puzzle, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology including Phyllis Lam, Marlene Jensen and Marcel Kuypers, teamed up with scientists from Kiel, Oldenburg, Hamburg, Aarhus (Denmark), Nijmegen, (the Netherlands) and Princeton (USA), to trace the individual reaction steps in the nitrogen cycle by following the fate of compounds labeled with the stable isotope of <sup>15</sup>N. Additionally, they identified the responsible microorganisms and active expression of the corresponding biomarker genes.

Left: On board of the German research vessel METOR scientists tracked the fate of the nitrogen in the Arabian Sea. After intensive analyses and interpretation they can explain the underlying processes. (Source: Leitstelle Meteor) Right: The water sampler collected samples at different depths.

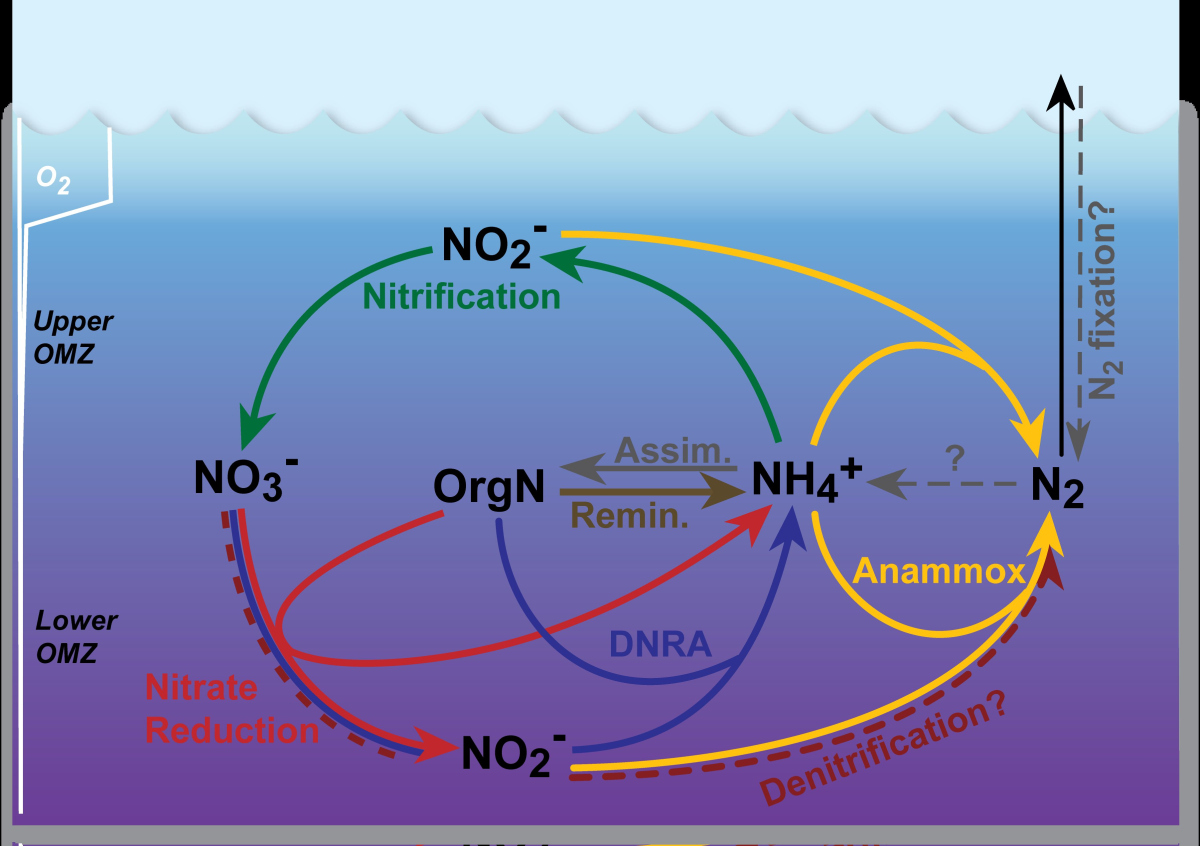

N-losses as a result of the coupling of two reaction pathways. In the Arabian Sea off the coast of Oman, DNRA (blue) provides ammonia for the anammox reaction (yellow), thus producing nitrogen gas N<sub>2</sub>that can escape from the water column. Nitrate reduction and nitrification also take place and act as sources of nitrite, and also of ammonia by the former reaction. Meanwhile, there is little evidence for denitrification activity (red dashes). (Source: modified from Lam et al., PNAS, 106:4752-4757).

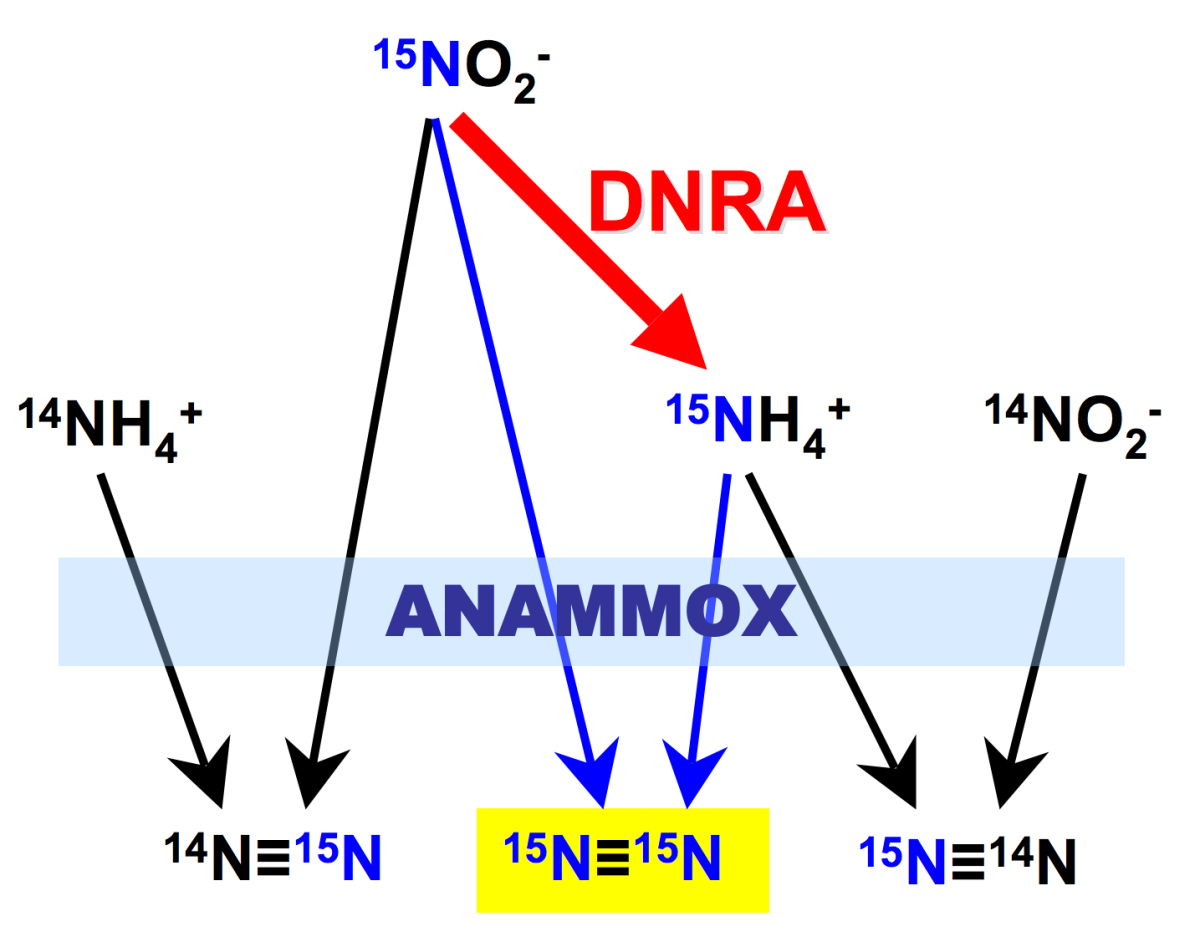

Labeling the nitrite with the stable isotope <sup>15</sup>N produced a double labeled <sup>15</sup>N-<sup>15</sup>N gas which could easiliy be detected by mass spectrometry. Previously thought to be a signature of denitrification, combined results from various <sup>15</sup>N-labeling experiments, stoichiometric calculations and gene expression analyses show that this is more likely a result of DNRA-anammox coupling. DNRA produces the <sup>15</sup>N-ammonia which will subsequently be combined with <sup>15</sup>N nitrite in the anammox reaction to yield the double labeled nitrogen gas.

Their findings were surprising. The central-northeastern area of the Arabian Sea, which was thought to be the stronghold, was proven to be almost inactive in N-losses during their visit. The scientists now explain the high nitrite concentrations found there by a slow nitrate reduction and little oxidation of ammonia. Both reactions can run under low oxygen conditions and form nitrite as a final product. Satellite data from the past 10 years show that surface phytoplankton production in this region is not particularly high on average. Due to such likely missing organic matter, nitrite cannot be reduced further. Together with the sluggish water circulation, nitrite therefore accumulates in this region of the Arabian Sea.

On the contrary, in the northwestern part off the coast of Oman, which was previously assumed to be irrelevant regarding nitrogen balances, the researchers detected very high N-loss activity. As shown in their publications, two coupled reactions in the nitrogen cycle can do the trick: the anammox reaction (anaerobic oxidation of ammonia) and the dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA). Like in a detective story, the scientists found the telltale evidence of <sup>15</sup>N-labeled compounds, as double-<sup>15</sup>N-labeled N<sub>2</sub> was formed from labeled nitrite through a combination of anammox and DNRA. DNRA provides the important ammonia for the anammox reaction, which needs both ammonia and nitrite to form gaseous N<sub>2</sub>. Further proof came from gene expression studies showing which microbial genes were actively engaged in the pathways. This DNRA-anammox coupling, in addition to some anammox alone, explains the high N-loss in these waters.

Dr. Marcel Kuypers, Max Planck director, says: “Our findings fit very well with our previous results from other OMZs like the upwelling regions off the coasts of Peru, Chile and Namibia, where we also found anammox to be the most important N-loss pathway. The high nitrite concentrations in the central-northeastern Arabian Sea are presumably the last traces of earlier events which are now leveling off.”

Dr. Phyllis Lam from the Max Planck Institute adds: “In the future, the Arabian Sea should remain in our research focus, as reactions therein have strong impacts on the global nitrogen balance. It is unlikely that active nitrogen cycling remains the same throughout the year with respect to the seasonal monsoons, and it will continue to alter with the increasing amounts of nitrogen inputs from the atmosphere and land due to human activities. Unfortunately, pirate activities will not allow further research expeditions in the area any time soon.”

Manfred Schloesser

Further information

Dr. Phyllis Lam

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Phone +49 (0)421 2028 644; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Marcel Kuypers

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Phone +49 (0)421 2028 602; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Marlene Mark Jensen

Technical University of Denmark

Phone +45 45251437; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Press officer

Dr. Manfred Schloesser, phone +49 (0)421 2028 704;

[Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

1. Original article

Origin and fate of the secondary nitrite maximum in the Arabian Sea. P. Lam, M. M. Jensen , A. Kock , K. A. Lettmann, Y. Plancherel, G. Lavik, H. W. Bange , and M. M. M. Kuypers. Biogeosciences, 8, 1565–1577, 2011

doi:10.5194/bg-8-1565-2011

Institutions

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

IFM-GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany

Institut für Chemie und Biologie des Meeres, Universität Oldenburg, Germany

Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, USA

2. Original article

Intensive nitrogen loss over the Omani Shelf due to anammox coupled with dissimilatory nitrite reduction to ammonium. Marlene M Jensen, Phyllis Lam, Niels Peter Revsbech, Birgit Nagel, Birgit Gaye, Mike SM Jetten and Marcel MM Kuypers. The ISME Journal (2011) 1-11. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.44

Institutions

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark

Institute of Coastal Research, GKSS Research Center, Geesthacht, Germany

Institute of Biogeochemistry and Marine Chemistry, University of Hamburg, Germany

Department of Microbiology, IWWR, Radbound University Nijmegen, The Netherlands

On the contrary, in the northwestern part off the coast of Oman, which was previously assumed to be irrelevant regarding nitrogen balances, the researchers detected very high N-loss activity. As shown in their publications, two coupled reactions in the nitrogen cycle can do the trick: the anammox reaction (anaerobic oxidation of ammonia) and the dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA). Like in a detective story, the scientists found the telltale evidence of <sup>15</sup>N-labeled compounds, as double-<sup>15</sup>N-labeled N<sub>2</sub> was formed from labeled nitrite through a combination of anammox and DNRA. DNRA provides the important ammonia for the anammox reaction, which needs both ammonia and nitrite to form gaseous N<sub>2</sub>. Further proof came from gene expression studies showing which microbial genes were actively engaged in the pathways. This DNRA-anammox coupling, in addition to some anammox alone, explains the high N-loss in these waters.

Dr. Marcel Kuypers, Max Planck director, says: “Our findings fit very well with our previous results from other OMZs like the upwelling regions off the coasts of Peru, Chile and Namibia, where we also found anammox to be the most important N-loss pathway. The high nitrite concentrations in the central-northeastern Arabian Sea are presumably the last traces of earlier events which are now leveling off.”

Dr. Phyllis Lam from the Max Planck Institute adds: “In the future, the Arabian Sea should remain in our research focus, as reactions therein have strong impacts on the global nitrogen balance. It is unlikely that active nitrogen cycling remains the same throughout the year with respect to the seasonal monsoons, and it will continue to alter with the increasing amounts of nitrogen inputs from the atmosphere and land due to human activities. Unfortunately, pirate activities will not allow further research expeditions in the area any time soon.”

Manfred Schloesser

Further information

Dr. Phyllis Lam

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Phone +49 (0)421 2028 644; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Marcel Kuypers

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Phone +49 (0)421 2028 602; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Marlene Mark Jensen

Technical University of Denmark

Phone +45 45251437; [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Press officer

Dr. Manfred Schloesser, phone +49 (0)421 2028 704;

[Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

1. Original article

Origin and fate of the secondary nitrite maximum in the Arabian Sea. P. Lam, M. M. Jensen , A. Kock , K. A. Lettmann, Y. Plancherel, G. Lavik, H. W. Bange , and M. M. M. Kuypers. Biogeosciences, 8, 1565–1577, 2011

doi:10.5194/bg-8-1565-2011

Institutions

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

IFM-GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany

Institut für Chemie und Biologie des Meeres, Universität Oldenburg, Germany

Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, USA

2. Original article

Intensive nitrogen loss over the Omani Shelf due to anammox coupled with dissimilatory nitrite reduction to ammonium. Marlene M Jensen, Phyllis Lam, Niels Peter Revsbech, Birgit Nagel, Birgit Gaye, Mike SM Jetten and Marcel MM Kuypers. The ISME Journal (2011) 1-11. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.44

Institutions

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark

Institute of Coastal Research, GKSS Research Center, Geesthacht, Germany

Institute of Biogeochemistry and Marine Chemistry, University of Hamburg, Germany

Department of Microbiology, IWWR, Radbound University Nijmegen, The Netherlands