- Press Office

- Press releases

- New Rhizobia-diatom symbiosis

New Rhizobia-diatom symbiosis solves long-standing marine mystery

Nitrogen is an essential component of all living organisms. It is also the key element controlling the growth of crops on land, as well as the microscopic oceanic plants that produce half the oxygen on our planet. Atmospheric nitrogen gas is by far the largest pool of nitrogen, but plants cannot transform it into a usable form. Instead, crop plants like soybeans, peas and alfalfa (collectively known as legumes) have acquired Rhizobial bacterial partners that “fix” atmospheric nitrogen into ammonium. This partnership makes legumes one of the most important sources of proteins in food production.

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, now report that Rhizobia can also form similar partnerships with tiny marine plants called diatoms – a discovery that solves a long-standing marine mystery and which has potentially far-reaching agricultural applications.

An enigmatic marine nitrogen fixer hiding within a diatom

For many years it was assumed that most nitrogen fixation in the oceans was carried out by photosynthetic organisms called cyanobacteria. However, in vast regions of the ocean there are not enough cyanobacteria to account for measured nitrogen fixation. Thus, a controversy was sparked, with many scientists hypothesizing that non-cyanobacterial microorganisms must be responsible for the “missing” nitrogen fixation. “For years, we have been finding gene fragments encoding the nitrogen-fixing nitrogenase enzyme, which appeared to belong to one particular non-cyanobacterial nitrogen fixer”, says Marcel Kuypers, lead author on the study. “But, we couldn’t work out precisely who the enigmatic organism was and therefore had no idea whether it was important for nitrogen fixation”.

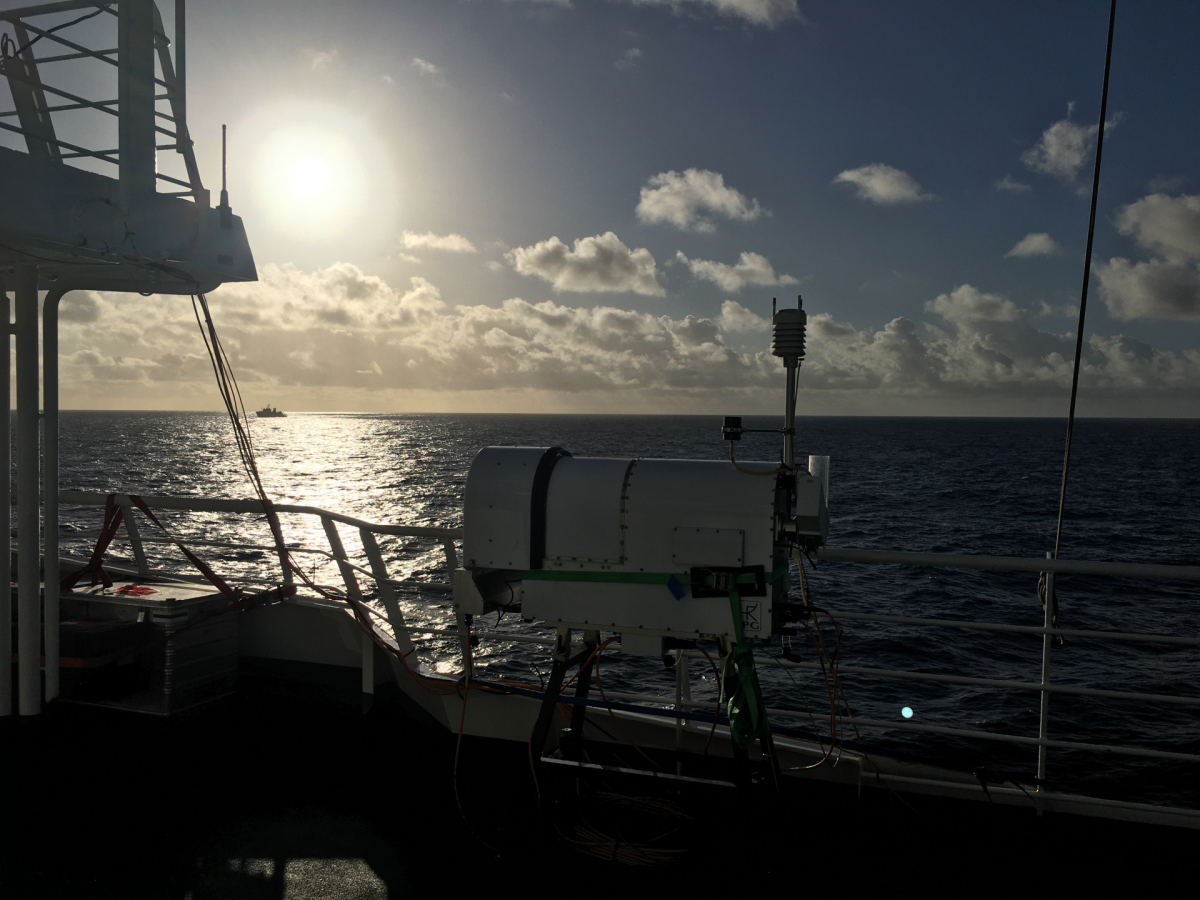

In 2020, the scientists travelled from Bremen to the tropical North Atlantic to join an expedition involving two German research vessels. They collected hundreds of liters of seawater from the region, in which a large part of global marine nitrogen fixation takes place, hoping to both identify and quantify the importance of the mysterious nitrogen fixer. It took them the next three years to finally puzzle together its genome. “It was a long and painstaking piece of detective work”, says Bernhard Tschitschko, first author of the study and an expert in bioinformatics, “but ultimately, the genome solved many mysteries”. The first was the identity of the organism, “While we knew that the nitrogenase gene originated from a Vibrio-related bacterium, unexpectedly, the organism itself was closely related to the Rhizobia that live in symbiosis with legumes”, explains Tschitschko. Together with its surprisingly small genome, this raised the possibility that the marine Rhizobia might be a symbiont.

The first known symbiosis of this kind

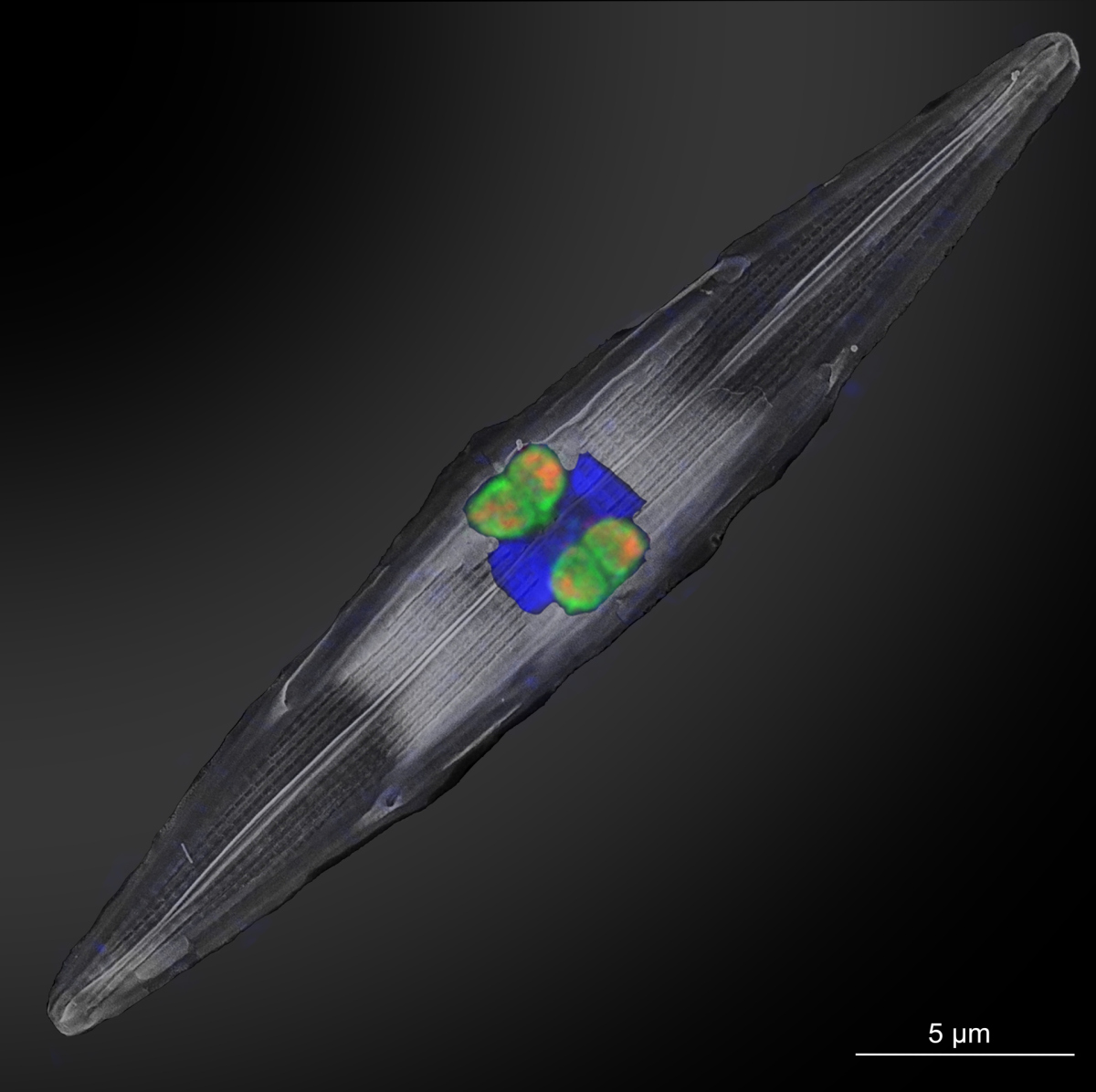

Spurred on by these discoveries, the authors developed a genetic probe which could be used to fluorescently label the Rhizobia. Once they applied it to the original seawater samples collected from the North Atlantic, their suspicions about it being a symbiont were quickly confirmed. “We were finding sets of four Rhizobia, always sitting in the same spot inside the diatoms”, says Kuypers, “It was very exciting as this is the first known symbiosis between a diatom and a non-cyanobacterial nitrogen fixer”.

The scientists named the newly discovered symbiont Candidatus Tectiglobus diatomicola. Having finally worked out the identity of the missing nitrogen fixer, they focused their attention on working out how the bacteria and diatom live in partnership. Using a technology called nanoSIMS, they could show that the Rhizobia exchanges fixed nitrogen with the diatom in return for carbon. And it puts a lot of effort into it: “In order to support the diatom’s growth, the bacterium fixes 100-fold more nitrogen than it needs for itself”, Wiebke Mohr, one of the scientists on the paper explains.

A crucial role in sustaining marine productivity

Next the team turned back to the oceans to discover how widespread the new symbiosis might be in the environment. It quickly turned out that the newly discovered partnership is found throughout the world’s oceans, especially in regions where cyanobacterial nitrogen fixers are rare. Thus, these tiny organisms are likely major players in total oceanic nitrogen fixation, and therefore play a crucial role in sustaining marine productivity and the global oceanic uptake of carbon dioxide.

A key candidate for agricultural engineering?

Aside from its importance to nitrogen fixation in the oceans, the discovery of the symbiosis hints at other exciting opportunities in the future. Kuypers is particularly excited about what the discovery means from an evolutionary perspective. “The evolutionary adaptations of Ca. T. diatomicola are very similar to the endosymbiotic cyanobacterium UCYN-A, which functions as an early-stage nitrogen-fixing organelle. Therefore, it’s really tempting to speculate that Ca. T. diatomicola and its diatom host might also be in the early stages of becoming a single organism."

Tschitschko agrees that the identity and organelle like nature of the symbiont is particularly intriguing, “So far, such organelles have only been shown to originate from the cyanobacteria, but the implications of finding them amongst the Rhizobiales are very exciting, considering that these bacteria are incredibly important for agriculture. The small size and organelle-like nature of the marine Rhizobiales means that it might be a key candidate to engineer nitrogen-fixing plants someday.”

The scientists will now continue to study the newly discovered symbiosis and see if more like it also exist in the oceans.

Original publication

Participating institutions

- Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

- Alfred Wegener Institute - Helmholtz-Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

Please direct your queries to:

Director

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3101 |

|

Phone: |

Scientist

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3135 |

|

Phone: |

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |