- Press Office

- 23.08.2016 Diversity of habitats at natural oil...

23.08.2016 Diversity of habitats at natural oil seeps

“The gas is partly converted to gas hydrates (an ice-like form of water and gas), which form small mounds on the sea floor. These are densely populated by meter-long tube worms,” explains Sahling. “Sometimes the mounds are prised, allowing a view into several-meter-thick gas hydrates, a very rare observation. The gas hydrates are overlain by a reaction zone where microbial communities convert methane, carbonate is precipitated, and dense colonies of tube worms develop. These keep the mounds together and live on reduced sulfur compounds. It is truly a remarkable habitat,” Sahling simmarizes.

In addition to the gas, also liquid oil escapes from the sea floor. It ascends slowly through small white chimneys, the drops of oil forming elongated threads or seeping through the sediments. “For organisms that are not adapted, the oil is harmful,” Sahling explains. “But the bountiful life at these sites shows that there are certain organisms that can thrive even on these hydrocarbons.”

The basis for this life is formed by microorganisms which degrade the various components of the oil. They are the focus of research at the MPI Bremen. Many of these microorganisms live anaerobically, i.e. without oxygen, in the oily sediments. Gunter Wegener from MPI Bremen currently investigates which microorganisms are actually using the asphalt and its constituents „What’s really exciting is that very different microorganisms – namely bacteria and so-called archaea – join forces to break up the hydrocarbons. We call this a syntrophy.“ Other bacteria degrading hydrocarbons cannot live without oxygen. As a result, their partnerships look quite different: They form symbioses with invertebrates. „We find these bacterial tenants in mussels and different sponges inhabiting the the oily crusts and blick of gas hydrates“, says Christian Borowski from MPI Bremen. „It’s noteworthy that these symbionts are closely related to bacteria that played a major role in degrading hydrocarbons in the Gulf of Mexico after the Deep-Water-Horizon-Oilspill.“ Researchers at the MPI Bremen now investigate, which metabolic pathways the symbiotic bacteria use, and which role the play fort he host.

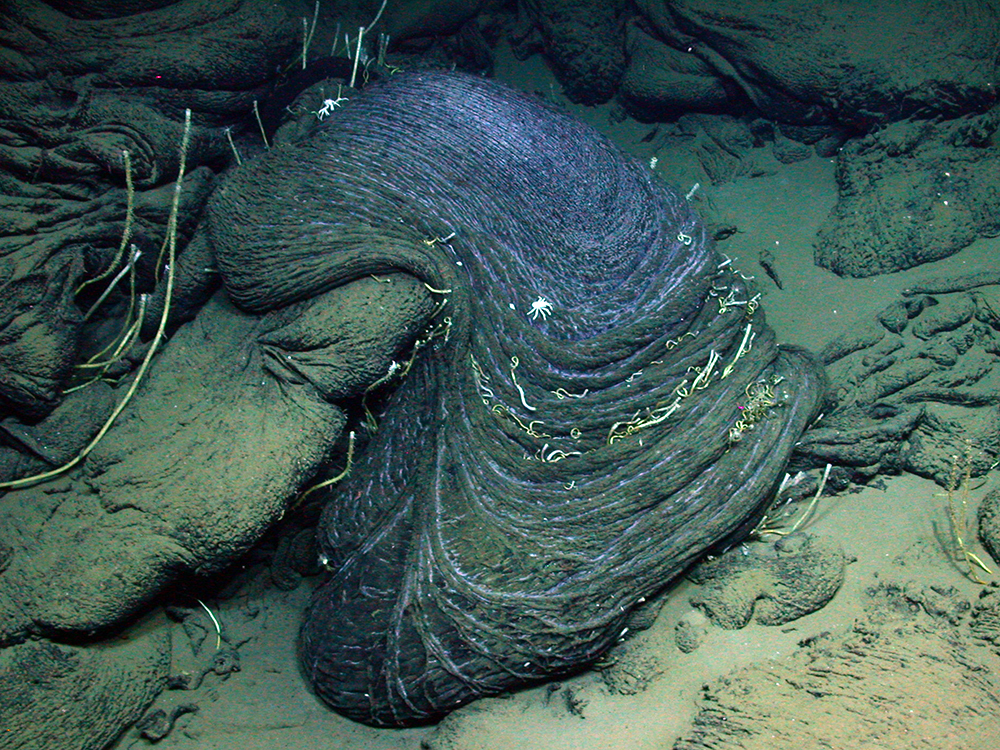

While these bacterial processes are not apparent to the eye, the oil seeps do allow for some spectacular views. Some components of the so-called “heavy oil” dissipate. What remains forms flow structures of asphalt on the sea floor. “During the expedition we documented many of these unique structures,” says Sahling. “The asphalt covers hundreds of meters of the sea floor and thus also forms a habitat that is colonized by tube worms and bacterial mats."