- Press Office

- Press releases 2019

- A flexible lifestyle in low-oxygen areas of the sea

A flexible lifestyle in low-oxygen areas of the sea

Arcobacter peruensis appreciates an inhospitable location. Where water appears to be a musty broth that contains little light and oxygen but is rich in sulfur, nitrate and plant remains - there it thrives. Such conditions exist in coastal shelf areas, where oxygen-poor upwelling water allows hydrogen sulfide to diffuse from the seabed into the overlying waters. Such conditions occur along the coast of Namibia and Peru, and it was in Peruvian waters where the microbiologists from Bremen and Kiel isolated this Arcobacter species, which they therefore named peruensis.

Better in competition

The researchers demonstrated that Arcobacter persuensis uses toxic sulfide they find in the water as a source of energy and transforms it into non-toxic elemental sulfur. At the same time, the microbe reduces nitrate to nitrogen gas, the latter of which is not suitable as a nutrient. Thus, Arcobacter peruensis also plays an important role in the nitrogen cycle. However the microbe surprised the scientists in one major point: it doesn’t fix carbon dioxide. "We tested if Arcobacter peruensis grows with carbon dioxide, as do many other bacteria with a similar metabolism," says Cameron Callbeck, first author of the paper, who now works at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. "But nothing happened."

Only when the scientists offered acetate, a fermentation byproduct, to the Arcobacter culture, did the bacteria begin to flourish." This shows that Arcobacter peruensis has a different lifestyle than its competitors. Therefore it has a clear advantage in low-oxygen but nutrient-rich environments with lots of organic material," says Callbeck.

Growing habitat

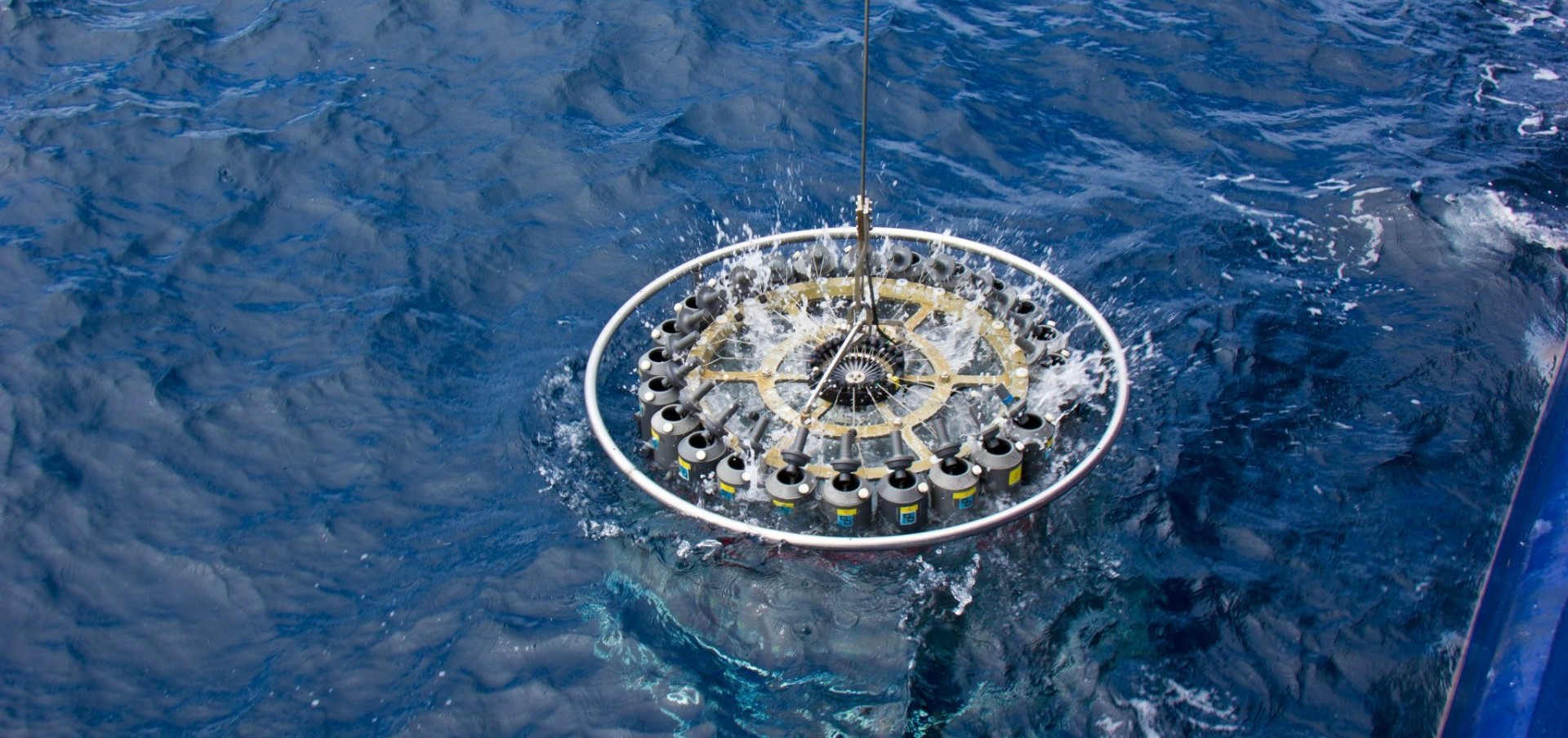

This would seem to be a very special habitat – and indeed it is. But such oxygen-poor habitats are expanding, especially in densely populated regions near the coast, where rivers transport fertilizer and wastewater into the sea. “Arcobacter peruensis may play a substantial role in the diverse consortium of bacteria that is capable of coupling denitrification and fixed nitrogen loss to sulfide oxidation in sulfidic coastal waters that are rich in nutrients,” says Gaute Lavik, cruise leader of the expedition of RV Meteor 93 to Peru. “A next step would be to study if this observation is correct elsewhere, and furthermore, to what extent Arcobacter peruensis influences the coastal nitrogen cycle.”

The paper is a result of the Collaborative Research Center 754 "Climate-Biogeochemistry Interactions in the Tropical Ocean", which commenced in 2008 and concludes at the end of this year.

Original publication

Cameron M. Callbeck, Chris Pelzer, Gaute Lavik, Timothy G. Ferdelmann, Jon S. Graf, Bram Vekeman, Harald Schunck, Sten Littmann, Bernhard M. Fuchs, Philipp F. Hach, Tim Kalvelage, Ruth A. Schmitz, Marcel M. M. Kuypers: Arcobacter peruensis sp.nov., a chemolithoheterotroph isolated from sulfide and organic rich coastal waters off Peru, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 85, iss. 24

Participating institutions:

Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology

Department of Microbiology, IWWR, Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands

Institute for General Microbiology, University of Kiel, Germany

Please direct your queries to:

Scientist

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3136 |

|

Phone: |

Scientist

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3127 |

|

Phone: |